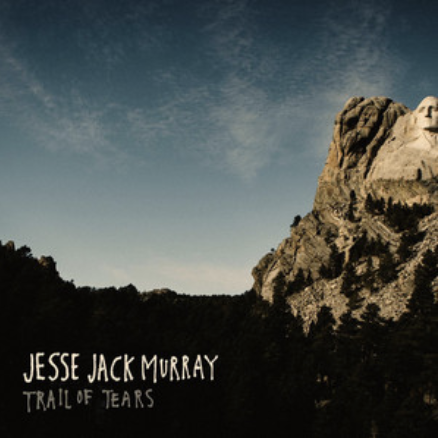

In 2018, I was sitting in a studio with some of Nashville’s best producers and artists, and one of them lamented, “Where is the protest music in the Church today?” Through most of modern music history, we can point to several artists who were a bit rebellious, unorthodox, and yet somewhat prophetic in the way they leveled criticisms toward religious subcultures. These voices are needed, and sadly have become harder to find. But one of those voices is Jesse Jack Murray. His new full-length album Trail of Tears – available now on Spotify – has been released through our friends at Renew The Arts, and is a thoughtful look at our historic and current prejudices toward Native Americans. I was so excited to talk to Jesse a few days ago, and here’s our conversation:

UTR: Your new album was largely inspired by your interaction and friendship with Native Americans. Can you tell us more about your experience?

Jesse: I moved to Rapid City, SD on my tenth birthday. My parents were educators and coaches and had been offered jobs working for Wesleyan Native American Ministries helping to run a small private school called Lakota Christian Academy. We weren’t Wesleyan at all– in fact I remember that aspect being oppressive and ultimately the reason my parents left Rapid when I was in college. The school wasn’t making little Wesleyans and there was a lot of drama around that.

But yea, that’s the world I grew up in. We lived with, and I grew up around Lakota kids and families. I was typically one of the only white kids in my crew (except on the legion baseball field), but that was perfect. I fit in or I didn’t. There were always seasons. But the Lakota culture was my world, and it shaped how I think, feel, approach practical life issues–– and it informed my worldview. In fact– it’s still re-informing my evolving worldview. The people I grew up around were beautiful, compassionate, funny, angry, oppressed, proud people. I am too. It was always weird though. I remember going places with my friends–– wherever, the mini-mart, the mall, etc.–– and I always knew that I was getting a better deal because I was white. I never drew seconds glances or had walls put up to keep me out. I remember some of the kids I played ball with used to make horrible jokes about the Native community, and it would piss me off–– but that was life there, the same as it had been in the old days, full of prejudice that had never been exercised from the culture.

.

UTR: Not many albums are thematically as cohesive or intentional as Trail of Tears. Can you describe the process or writing & creating the project?

Jesse: The journey of this album has been like a 10 year process. When I got to college, I fell in with a group of kids that showed me how to write songs, and so I started writing. This had been my life- so these songs just started coming. The oldest tracks on the record are Cheyenne River and Horace Mann which I wrote as a junior/senior in college. The rest of them just started coming year by year, and then one day, Justus Stout from RTA said, “Jesse, we need to make a record.” After he put that to life, I started getting a little more intentional about honing a vision. I wrote 54/40, Snowblindess and Trail of Tears (with some help from J. Stout) while I was living in Dayton, TN shortly after my daughter Sundance was born. At that point, I knew we were going to make a record and I wanted it to be as ruffling and protestant as it could be while still just being a subjective, recounting of my own story. It just happens that a huge part of my story was growing up with a nation of people who had been terribly wronged by our government and the Church. So, the cohesion of this album is almost accidental–– or maybe providential. I don’t know.

UTR: What do you hope are some of the emotions and thoughts the listener has when absorbing Trail of Tears?

Jesse: Any emotion is good. Just to feel something is the point–– to create a space in your heart for the Indigenous peoples of your country. One of the huge obstacles that has faced Indigenous groups in America is that no-one is talking about them. It’s crazy how little national attention their communities get. I remember keeping up with Standing Rock and DAPL. We even held a protest at the army corp of engineers in Charleston, SC. And when the whole thing was done, it was done. That was it. Their people and their issues aren’t held sacred in the hearts of most Americans, which makes no sense to me. They are our sisters and brothers. They basically have to engage in armed stand-offs or occupy Alcatraz to get the world to listen. Another thing I would like to play any small part in doing is destroying the patriotic narrative that many Americans hold on to so dearly. Just understanding the history of displacement and the role the American government and “Church” played in all but destroying an entire civilization will be helpful for the new generation. It’s not about hating white people or disowning our ancestors or despising our county- it’s about recognizing terrible fault and pursuing collective repentance as a nation. To quote the Avett Brothers: “Love in our hearts with the pain and the memory.”

UTR: You are clearly okay with music ruffling some feathers (in a good way). How do you see modern protest music helping to serve the Church?

Jesse: I don’t know honestly. Songs don’t change the world, but they do change peoples’ minds. So, I can speak for myself and for this album. I want to see decolonization in the Church. One thing I learned growing up is that white Christianity is just that. It’s for white people. And that’s cool because a lot of us are white. But growing up in the shadow of a Wesleyan ministry, I so often saw and heard stories of higher ups who would come from Indianapolis and berate the people running the schools and churches for not discipling better “Wesleyan Indians”. And that’s been the perspective of the American Church at large from the get go. It’s the same in other countries too. You have people coming in (some with great intentions and hearts bursting with love/ some cutting hair and beating children for speaking their native tongue)–– and they kill themselves trying to bridge a cultural gap that doesn’t need to be bridged. The path of Jesus can be walked to the beat of any drum. It has always been this way. Maybe my perspective of universal salvation informs this in me, but the heart of Jesus is for all people, in all times and all places. He is ever-available and ever-patient. I loved what Rich Mullins said once in an interview when he was asked why he had moved to the Navajo reservation. He said, “I just kind of got tired of the white, evangelical, middle-class perspective on God, and I thought maybe I would have more luck finding Christ among the pagan Navajo.”

.

UTR: The style and content of these songs likely translate well to a live setting. How might people reach you to host you in their living rooms or churches?

Jesse: I love to travel, and I work from home so if anyone wants to pay for our gas and give me and Dhember and Sundance a place to crash, we would love to come see you and fellowship with you and play you some music. 😀

Jesse Jack Murray lives in Belle Glade, Florida with his wife and daughter. He can be found on Facebook and on Bandcamp.

Leave A Comment