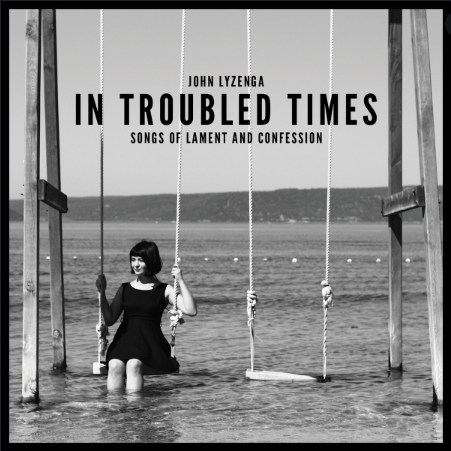

I love the quote from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The Church can at times become so focused on its inner culture that it hides its eyes from the need for cultural reform. John Lyzenga is a singer-songwriter that is doing something that we rarely see in the Church world – he is giving congregations an opportunity to unify their voices on issues of social justice through worship songs. His 2019 release In Troubled Times (available on Spotify) has been one of the most unique and pointed worship albums we have heard this year, and I’m so excited we could interview him this week (and happy he dropped a quote from Dr. King as well).

UTR: Who are some of your musical influences as you were growing up?

John: Conor Oberst and Sufjan Stevens were and still are very influential for me both lyrically and musically. I relate to Conor Oberst’s persistent questioning of religious institutions, cultural norms, the government, and even his own worldview. And while Conor Oberst’s critiques and questionings seem to have led him away from institutionalized religion, my concerns with Christianity have forced my faith to adapt kindling in me a desire to be a part of a more inclusive and justice-oriented Christianity. In this way, I have found commonality with Sufjan Stevens as a songwriter who is both known for his more progressive values and also vulnerably expressing his own faith and struggles with the Church.

UTR: When did the idea of writing songs of worship develop?

John: I started writing worship songs in the fall of 2016, which may seem odd to anyone who knows me as I’ve been writing non-worship songs and leading worship since I was a teenager. What deterred me from writing worship music for so long is that it is such an overcrowded market, especially with white, male singer-songwriters. If I was going to do this, I had to add something meaningful to the conversation. So instead of trying to lean away from my whiteness, I actually wrote songs intentionally for white congregations inviting them to locate themselves both in scripture and in our current societal context. This inspiration grew from simultaneously occurring events—starting my Master of Divinity program at San Francisco Theological Seminary, awakening to my own privilege as a white, straight male, and also the depths of American Christianity’s sins in response to such events as the Flint water crisis, the Black Lives Matter movement, the Charlottesville protests, the North Dakota Access Pipeline, and violence against the LGBTQ community. So it was in this void that I drew from my biblical studies and my background as a songwriter and worship leader to write congregational worship songs that named and addressed the disturbing realities going in our country. It was never about writing songs that pushed progressive values but really about expressing what I experience to be the gospel message, one of justice and love.

UTR: How do you feel the worlds of justice and advocacy intersect with music?

John: In my experience, music provides space for listeners to hear difficult truths inviting us to reflect on ourselves, our worldviews, and how we impact others. Worship music goes a step further as it is music for communal singing providing us with the language for how we express our faith and thereby how we engage or disengage with the world and issues of social justice. In the Church, we typically sing songs of praise about God’s greatness and faithfulness and we seldom sing songs questioning God’s providence or confessing communal sins. It makes sense that this would be our norm, but how do we proclaim God’s faithfulness when tragedy occurs? How do we respond? Throughout our society and its history, we have seen some Christians respond by ignoring such suffering entirely. Those Christians who are in positions of privilege are especially susceptible to such ignorance since they (including myself) often do not experience the struggles of those on the margins. When we only sing praise, we are in danger of neglecting and even negating those who are in real suffering. We must expand our dialogue to include the language of lament which is found all throughout scripture. Not only do we then open our hearts to the experiences of the marginalized, but we open ourselves to our own sufferings. Adding lament to our vocabulary makes us more outward-oriented people making us dissatisfied with the things of this world that are not of God’s kingdom and therefore urging us forward to participate in its fulfillment.

UTR: What is the overall vision and goal for your latest album?

John: In Troubled Times provides worshiping communities with biblically-based worship songs that move Christians to participate in God’s justice work. While there are many social issues addressed on the album, the pervading thread is privilege and race inviting congregations to ask the question, “How do we individually and communally engage social justice issues as those who benefit from systemic and institutional inequality?” When I first started writing the album, it was going to be solely a worship protest album particularly drawing from scriptural texts of lament. However, in conversations with my professor and editor, Rev. Yolanda Norton, she expressed to me the importance of naming one’s own perpetuation and benefit of oppressive systems before joining its the voices of the marginalized. Given the subtitle, the album then becomes a collection of songs of both lament and confession. These songs invite congregations to reflect and confess their role in oppressing others before they stand with particular movements. The hope is that we, as Christians, will be known for the way we love others and stand with those who are being oppressed.

UTR: Some topics and song lyrics on this album aren’t afraid to challenge the status quo of the Church. Have you received any push-back or friction for these bold choices?

John: In reactions to the album, people seem to fall into three categories. Some have responded with excitement expressing that they have been longing for social justice-oriented worship music. Some have responded with disinterest likely over a difference of political or theological values, and others have responded with a kind of anxious interest. This last group often affirms that these issues are important but are not quite sure about bringing them up in corporate worship. Before the album came out, I was asked to lead “To See the Bound Made Free” at a local congregation. The lyrics had been passed around the church staff and apparently there was some concern with the bridge in the song stating “you gave for all Black lives/ you gave for refugees/ you gave for LGBT/ you set prisoners free…” While those on staff believed in these affirmations, there was hesitancy around declaring them in worship. They asked if I would lead the song without the bridge. I responded explaining the importance of affirming this truth publicly, especially during delicate times in our society. I then offered them this quote by Martin Luther King, Jr. “We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history, there is such a thing as being too late. There is no time for apathy or complacency. There is a time for vigorous and positive action.” They graciously allowed me to lead the song in its’ entirety and it was extremely well received by the congregation. I do not think we live in a time when we can delay talking about societal issues. While these may seem like issues for the Church to discuss and ponder over while it goes about the day-to-day, these are the lived realities of real people in our country and throughout the world. The longer that we delay in affirming God’s love for all creation, the more irrelevant we become by the hour.

UTR: If a local church wanted to be more intentional about social justice issues, what are some words of advice?

John: If congregations want to be more intentional about social justice issues, I would first encourage them to partner with local social justice organizations that are already doing this kind of work. Many of these kinds of organizations have experience educating congregations on particular issues and how they can get involved in both individual and communal ways. I also believe that worship is the most important moment in the life of the congregation, and if social justice issues are not being named there (sermons, songs, prayers, etc.) then it will be no surprise that congregants will not believe these forms of mission to be vital. In many larger churches, Christian formation, mission, and worship are divided into different departments, but there must be a common vision for each of them as they all inform one another. Our worship practices shape us into the type of Christians we will be and that informs how we engage or disengage with the world and especially our local community.

John Lyzenga, his wife Michelle, and infant son reside in San Fransisco. More information about his music and ministry can be found at johnlyzenga.com.

John is the salt of the earth. A gentle and kind person, passionate about social justice and his music is fire.

I’m so grateful for leaders in the church like John who are challenging the status quo and providing resources for the church to sing & pray what is so often not sung or prayed. It is challenging me as a worship leader in a canadian context to think more deeply about my role in helping people worship God in spirit and in truth.

I love that John is seeking to embody in his songwriting what King called for (as John quotes him): “We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history, there is such a thing as being too late. There is no time for apathy or complacency. There is a time for vigorous and positive action.” This album will assist congregations—perhaps especially white congregations—in the process of reflecting, confessing, and engaging.